By Lucia Espino

Una educación bilingüe es más que traducir palabras de un idioma a otro. Se trata de entender el significado del lenguaje a nivel académico, al igual que la cultura de donde proviene.

Desde que Galilea Guerrero, 7, comenzó a ir a la escuela, sus padres Brenda Esquivel y Cesar Guerrero sabían que lo mejor para ella sería una educación bilingüe.

Al empezar el pre-kinder Galilea sólo hablaba español, Esquivel dice que su transición de este idioma al inglés ha sido sencillo. “No le costó trabajo…cuando menos lo esperamos ya nos hablaba inglés sin darse cuenta”.

Guerrero y Esquivel dicen estar satisfechos con la educación que Galilea ha recibido en la escuela primaria Bob Hope en el distrito escolar independiente del suroeste de la ciudad. “Me gusta mucho que no dejan de lado su español, realmente está aprendiendo en los dos idiomas”, dice Esquivel.

Es por esta razón que la escuela de educación en la Universidad de Texas A&M en San Antonio, se asegura que su programa de educación bilingüe certifique a maestros que no sólo hablan español pero que sepan enseñar académicamente en español.

Este programa de educación bilingüe enseña a futuros maestros como ayudar a estudiantes que están aprendiendo otro lenguaje o a aquellos que quieren mantener sus dos idiomas, en la gran mayoría de los casos se trata de inglés y español, según la Dra. Esther Garza, profesora asistente de educación bilingüe y del programa de inglés como segundo lenguaje (ESL) de la universidad.

Y ella no esta equivocada, de acuerdo con el Censo del 2010, 63.2 por ciento de la población en la ciudad es de origen Hispana y a nivel nacional el español es el segundo idioma más hablado.

Garza dijo que el programa se asegura que futuros maestros interesados en esta área sean eficientes en el idioma español para que puedan aprobar el examen llamado Bilingual Target Language Proficiency (Dominio del Idioma en Objetivo Bilingüe).

Este exámen le permite al estado saber si el futuro maestro está listo para enseñar en una aula bilingüe. Recientemente, el estado agregó la sección de escritura al examen que antes sólo incluía entender, hablar y leer español.

Aquellos que no son eficientes en español, pueden obtener un certificado de ESL, dice Garza. “En los últimos cuatro años, hemos visto un incremento en aquellos buscando no solo un certificado en educación general pero también uno en ESL”.

Futuros maestros en el programa son entrenados en comprender la cultura de los que serán sus estudiantes. Al entender el tipo de comunidad de donde vienen su estudiantes, es más fácil comprender el lenguaje y enseñarles.

Muchos de estos futuros maestros se interesan en el programa bilingüe porque ellos pasaron por la misma experiencia, dice Garza.

Esta opinión es compartida por Carolina Carranza, maestra de primaria bilingüe, quien se graduó de este programa el pasado mayo y actualmente está en el proceso de obtener su certificado.

Nacida en México y traída a los Estados Unidos al comenzar su séptimo grado de educación, Carranza dice entender que aprender un lenguaje nuevo es más que un cambio de idioma, es un cambio de cultura.

“Al pasar por la situación por el cual la mayoría de nuestros estudiantes bilingües pasa, eso me hace sentir completamente capacitada para ser una maestra bilingüe”, dijo Carranza.

Esquivel y Guerrero dicen que las maestras de Galilea han sido Hispanas, y sienten que esto ayudó a que se desenvolviera en un ambiente bilingüe.

Normalmente la educación bilingüe sólo es ofrecida hasta el sexto grado, pero un proyecto de ley llamado Sello del Bilingüismo en Lectura y Escritura del estado reconoce a aquellos estudiantes de preparatoria que demuestren esta abilidades.

“Sería un sueño si la educación bilingüe estuviera hasta que se graduarán de la preparatoria”, dice Garza, quien resiente el haber sido sacada del programa durante el tercer grado en su niñez.

En el 2007, la oficina del Censo reveló que en esta ciudad el 39.5 por ciento de los negocios le pertenecen a Hispanos.

Por esta razón, Carranza dice que este tipo de educación debería llegar hasta la universidad, especialmente si se vive en esta ciudad. “Vivimos en una ciudad donde hay muchos latinos y la verdad yo considero una desventaja el no hablar español”.

Por ahora, Galilea seguirá en educación bilingüe hasta que su escuela considere que esta lista para clases completamente en inglés. Pero sus padres dicen temer que ella olvide su español si no continúa con su educación bilingüe.

“Queremos que mantenga los dos idiomas porque, no importa lo que ella decida hacer para su futuro, ser bilingüe siempre le va a ayudar”, Esquivel comentó.

Translation

Opinion: Bilingual education, more than translated words

A bilingual education is more than just translating words from one language to another. It’s about understanding the meaning of a language in academics, and the culture from where it comes from.

Since Galilea Guerrero, 7, started going to school, her parents Brenda Esquivel and Cesar Guerrero believed bilingual education was the best for their daughter.

When Galilea started pre-kindergarten she only spoke Spanish, but her transition from this language to English was smooth, Esquivel said. “It wasn’t hard for her…when we least expected she was speaking English to us without even noticing.”

Guerrero and Esquivel said they are satisfied with the education Galilea is receiving at Bob Hope Elementary School, located in the Southwest Independent School District. “They don’t put her Spanish aside and I like that, she is really learning in both languages,” Esquivel said.

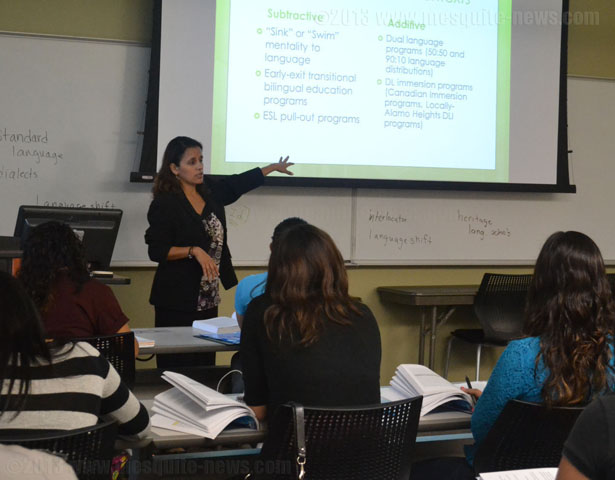

This is because, the college of education at Texas A&M University-San Antonio is making sure students obtaining a teacher’s certification not only speak Spanish, but know how to teach in Spanish.

The bilingual education program is training future teachers on how to help students who are learning a new language, or those who want to keep both languages. The majority of the cases are between English and Spanish Esther Garza, assistant professor in Bilingual/ESL Education said.

Garza’s statement goes hand-in-hand with information from the 2012 Census, which states 63.2 percent of the city’s population is Hispanic and that Spanish is the second most spoken language in the U.S.

Garza said the program makes sure future teachers interested in this field are Spanish proficient. In order to be certified as a bilingual teacher, they must face the Bilingual Target Language Proficiency Test.

This state-level exam evaluates the ability to teach in a bilingual classroom. Recently, a writing section was added to his exam, which only tested on reading, speaking, and understanding.

Those who are not Spanish proficient, can be certified as an ESL teacher, Garza said. “In the last four years, we have seen an increase in those looking not only to be certified in general education, but also to be certified in ESL.”

Future teachers are also trained to understand the culture of their students. Getting to know the community around their students allows teachers to better comprehend the origin of their language.

Many of these future teachers became interested in the bilingual program because they have been through the same experience, Garza said.

Carolina Carranza, elementary bilingual teacher, agrees. She graduated from the program Spring 2013 and is in the process of obtaining her certification.

Born in Mexico and brought to the U.S. when she began seventh grade, Carranza understands learning a new language is more than learning words, it is also a change in culture.

“Having gone through the same situation the majority of these bilingual students goes through, makes me feel even more capable to be a bilingual teacher,” Carranza said.

Esquivel and Guerrero said the teachers Galilea had thus far are Hispanic, and believe this helped their daughter’s bilingual development.

Normally, bilingual education is only offered until sixth grade, but House Bill 921 or Seal of Bilingualism and Biliteracy recognizes high school students who demonstrate these abilities.

“It will be a dream if bilingual education was offered until high school graduation,” Garza said, who resents being pulled out of the program in third grade.

In 2007, the Census Bureau reported that 39.5 percent of businesses in the city are Hispanic-owned.

For this reason, Carranza said bilingual education should even be offered in higher education. “We live in a city where there is a lot of Latinos, and not speaking Spanish is a disadvantage.”

For now, Galilea will continue her bilingual education until she is ready take on a full English course. On the other side, her parents said they are afraid she will forget her Spanish if she doesn’t continue her bilingual education.

“We want her to maintain both languages because, no matter what she decides for her future, being bilingual is always going to help her,” Esquivel said.